On bonfires

Argentinian festivals, Chinese funerals

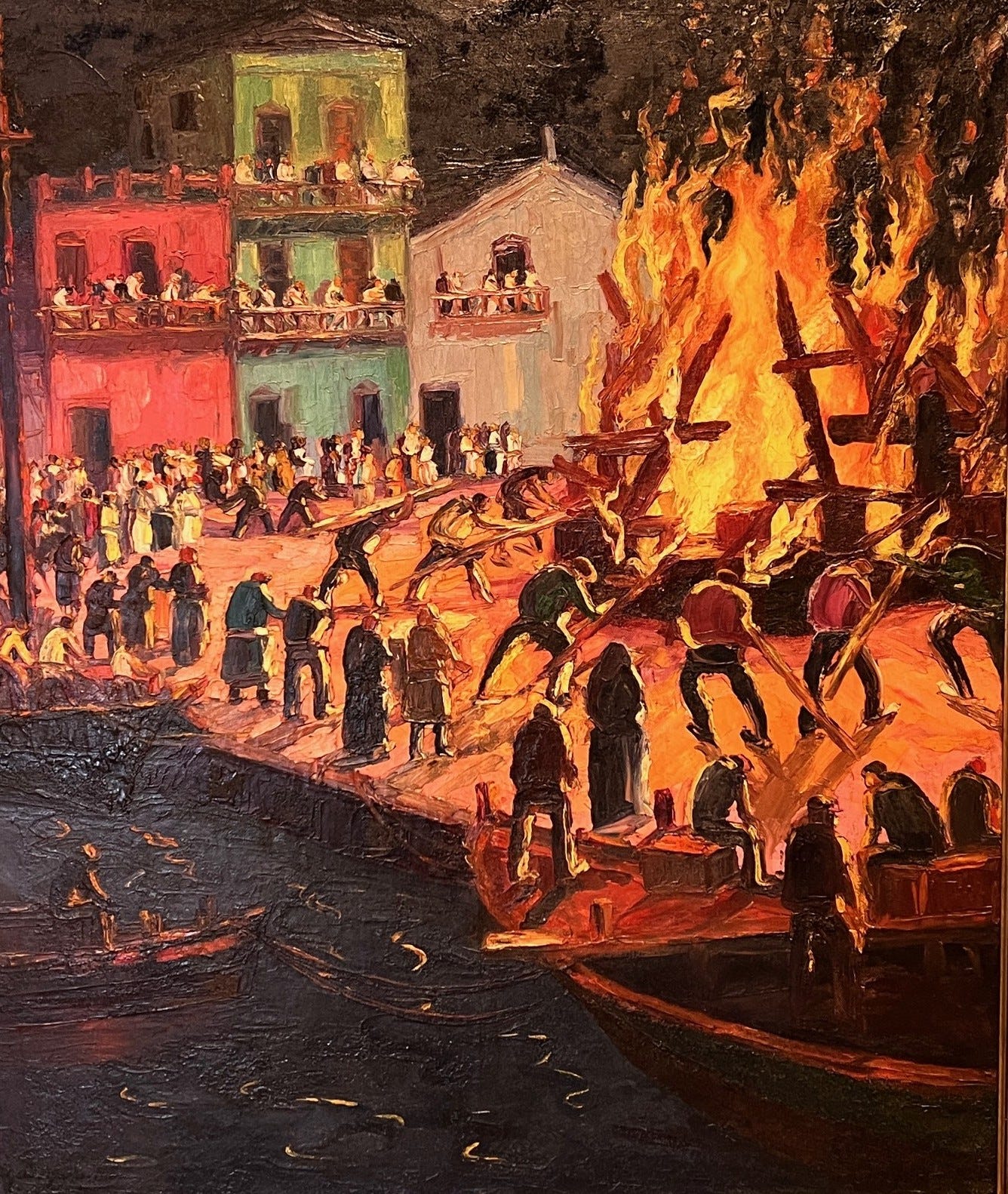

In the heart of La Boca, hanging in the home-turned-museum of late artist Benito Quinquela Martín, sits a remarkable oil painting of a bonfire, surrounded by faceless silhouettes in the port, “the mouth” of Argentina. In the same exhibit, a few feet away, sits a similar painting by another artist, of an uncontrolled, accidental fire that devastated the neighborhood.

But the fire Martín paints is intentionally set, in fact, depicting a celebration of the San Juan1 Festival in late June — flames fed by old furniture, unwanted objects, and wishes. People jump over the lick of flames, bathe in the sea, and partake in music and dance around the bonfire. The custom originates from and is also widely celebrated in Spain, believed to have pagan roots in honoring the sun and warding off evil; it is an act of spiritual renewal.

The word “bonfire” intuitively signals “good fire”, but actually originates from the medieval term “a fire of bones” from Celtic festivals in which animal bones were burned in a symbolic sacrifice to ward off evil spirits. Since the Middle Ages, and likely before the existence of written language, transformational worship has been tied to immolation.

The human occupation with bonfires is pervasive. A key proponent of a Chinese funeral2 is the burning of paper money (joss), one of many offerings made at the graves of ancestors. In addition to joss, paper recreations of all things one may need in the afterlife — cars, buildings, even paper smartphones — are ceremoniously tossed into a bonfire at the site of burial.

The beginnings of the fire are stoked first by joss paper, fed one by one then in stacks, until the flames are large enough to devour the larger fixtures — shiny recreations so brightly colored they nearly feel out of place at a site of grieving. An elaborate feast of tea and baijiu3, of the best-looking fruit and traditional snacks, is also laid out; after the paper menagerie is burned, family members gather to carve the sweetest part of dragon fruit or crumble pieces of decorated pastry into the fire, passing them to the afterlife — along with beloved belongings, such as paintbrushes and oft-worn clothing. In the final act, white funeral robes are burned in purification of the bereaved.

In both the San Juan festival and in Chinese funerals, in celebration and in grief, people start bonfires for another entity — as sacrifice for pagan spirits or in honor of a passed relative, it is expressly done in service of another. But it is also for those who set the fires and need to see a thing of beauty, of discomfort, of fury and destruction, to feel true change in phoenix fashion — true rebirth.

Are we better able to understand a loved one is gone when we see the fruit char, the paper shrivel? Even as heat seeps into the skin — a warmth of acceptance and finality, or perhaps, of community and persisting love — it is kept bittersweet by the stinging in the eyes, the closing of the throat. Smoke reminds the fire-setter that this warmth comes not without sacrifice, not without some destruction.

In Martín’s painting, the little figures have their heads cowed, their silhouettes outlined by a halo of firelight. It is at once a grand affair and a solemn one. Some Promethean instinct compels us to contain the power of destruction in an ethereal sigil. It asks of us to transmute sacrifice into purifying creation.

In my family’s region, smaller “bonfires” are set in the days following the funeral along the coast of the Yellow River: torn bun pieces steamed in a metal spoon, red wax candles lit up and erected into the sand. Each time, the sight of a flame is mesmerizing; fire takes on a quality unlike any color or dimension. It lacks the hard edges of our tangible world, and against the pitch black of night, aches to look at directly. Yet, it’s impossible to look away, to mutter anything but prayer over the wind-muffled cry of burning.

The effect is otherworldly — we get to our knees and touch our foreheads to the coarse ground, for these motions are spiritual release. These bonfires are worship.

Also known as St. John’s or Sant Joan celebrated June 23-24 annually

Different areas of China perform different variations of this ritual

Clear Chinese distilled liquor